Abernethy Forest: A Visit and some after reading

Ken Thomson

In April 2023, about a dozen NEMT and Cairngorm Club members visited the RSPB reserve at Abernethy, which includes Strathnethy and the Loch Avon basin. The long-term RSPB aim here is to create the largest area of native woodland in Britain, with its ornithological and many other benefits. We met at Forest Lodge — built in 1883, used by the Norwegians during the Second World War, and now the largest all-timber dwelling house in Scotland. There, Uwe Stoneman, the Senior Site Manager, gave us an interesting talk about himself, the Lodge, and RSPB activities on the estate.

After the talk, we went out — in warm spring sunshine — on a 3-hour circular walk via Rynettin, stopping occasionally for Uwe to point out items of interest, and the group to discuss. Most of the conversation focussed on trees, deer and indeed cattle, which the RSPB are introducing in places within the forest, to see what effects they have on shrubs and seedlings — primarily of course to benefit rare species such as capercaillie and the crested tit. We heard some interesting tales, such as winching down trees to mimic the effects of storm windthrow, restoring peat on the hills east of Bynack More, and planting rather than waiting for natural regeneration.

The ever-increasing number of activities being undertaken by the public on RSPB land, and "land reform" pressures generally, are encouraging RSPB to take a more "community engagement" line (for instance, see Visitor & Access Plan). Two RSPB rangers have been appointed to help visitors (and especially their dogs, during the ground nesting season!) on the Cairngorm plateau (see video). Uwe "would be interested to understand how you and your members feel about these topics" and others such as climate change impacts on species such as dotterel, snow bunting, ptarmigan and mountain hare, and erosion on and off mountain paths.

The group in the forest © Ken Thomson

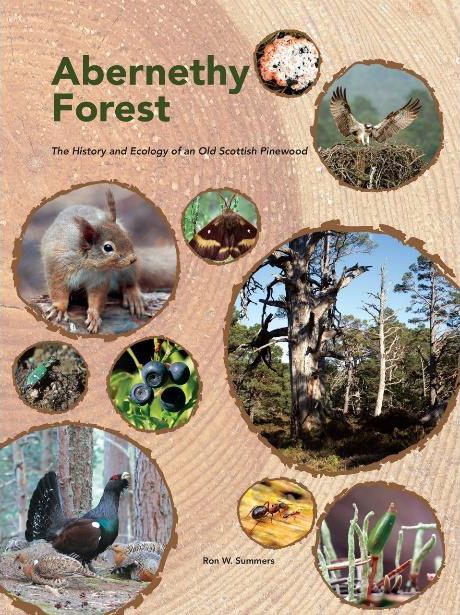

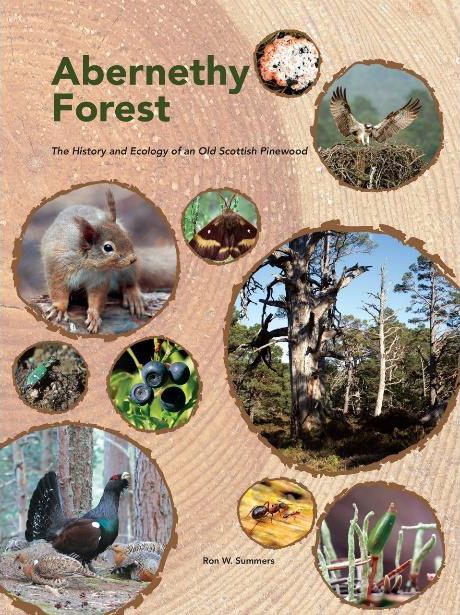

Since the visit, I have acquired "Abernethy Forest: the History and Ecology of an Old Scottish Pinewood" by Ron W. Summers (360pp; RSPB; ISBN: 9781999988203), a readable compendium of many aspects of the Forest, both its ecology (e.g. fungi, plants, invertebrates, mammals) and its human aspects (history, management). It is far too massive to summarise here, but some nuggets include:

Since the visit, I have acquired "Abernethy Forest: the History and Ecology of an Old Scottish Pinewood" by Ron W. Summers (360pp; RSPB; ISBN: 9781999988203), a readable compendium of many aspects of the Forest, both its ecology (e.g. fungi, plants, invertebrates, mammals) and its human aspects (history, management). It is far too massive to summarise here, but some nuggets include:

- The Scots pine area which dominates the forest peaked between 8000 and 5500 ago, and may have arrived from a "glacial refugium" in Wester Ross (rather than from the south); the area then declined, perhaps more due to human land use (livestock grazing, and burning) than to the cooler, wetter climate.

- Felling, and (from 1763 onwards) planting has left little "ancient native pinewood" at Abernethy, and very few large-girth trees. Summers prefers the term "Caledonian pinewoods" to cover both the fragments of naturally established pines from the once-extensive "Caledonian forest" and trees established, naturally or planted, in areas once felled, burnt, or grazed out.

- The Grant family owned the Abernethy estate between 1516 at the latest through to 1969, when they sold the forest to the Naylor family, who in turn sold 8258 ha to the RSPB in 1988, with more added later. The long period of single-family ownership probably accounts for the survival of the Forest as such, despite much human usage over the centuries, since considerable regulation and enforcement was exercised, especially over conflicts with farming, game-shooting and fishing.

- Local usage of the Forest included local timber for building, carts, home fires (if not peat) and light (fir-candles), while later, more commercial usages involved timber (floated down-river or sawmilled) for shipyards, smelting (e.g. of iron ore from the Lecht), railways, etc. — with Canadians (who built a rail network) and prisoners of war used during the two World Wars"

- Broadleaved trees (e.g. willow, birch, alder, aspen and rowan) are rather scarce in the Forest, but about 400 species of bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) have been recorded, plus ferns, herbs and shrubs (mainly heather, blaeberry, cowberry and juniper). Knowledge of fungi and lichen is less advanced; a 21-year period showed no decline in the number of new species of agarics and boleti recorded in Abernethy Forest each year, to a cumulative total of nearly 500. Similarly, about 450 species of epiphytic lichens have been recorded on Caledonian pinewoods.

- Over 900 species of beetle have been described at Abernethy (out of about 400,000 worldwide!), and many rare species of invertebrates, which include slugs, spiders, ticks, insects (e.g. butterflies, ants, bees, worms and mites), particularly those dependent on deadwood.

- After taking over the Forest, the RSPB culled red deer to below half previous densities, to encourage natural regeneration of shrubs and trees. Foxes and crows were also culled, and deer viscera (gralloch) removed, to reduce predation of capercaillie and black grouse eggs. The aim is to extend the Caledonian pinewood to the potential treeline, thus doubling the wooded area.

- Naturally, birds are the primary focus of the RSPB In the Abernethy Forest, both the "big three" — the capercaillie, crested tit and (three species of) crossbill — and the osprey, grouse, goldeneye, etc. which use the trees as a base but venture further afield. Breeding success for such species has been patchy, and may depend on expanding the area of Caledonian pinewood, preventing the return on non-native conifers, and waiting for older trees and deadwood, previously discouraged by human intervention, to appear.

The above items simply highlight a few points in a fascinating book. Some difficult issues remain, e.g. the roles of fire, disease, climatic change and re-introduced species (e.g. beavers, lynx), and the management of human visitors to an increasingly attractive area.

NEMT Front

Page | Previous Page | Volume

Index Page | Next Page | Journal

Index Page

Please let the webmaster know

if there are problems with viewing these pages or with the links they

contain.

Since the visit, I have acquired "Abernethy Forest: the History and Ecology of an Old Scottish Pinewood" by Ron W. Summers (360pp; RSPB; ISBN: 9781999988203), a readable compendium of many aspects of the Forest, both its ecology (e.g. fungi, plants, invertebrates, mammals) and its human aspects (history, management). It is far too massive to summarise here, but some nuggets include:

Since the visit, I have acquired "Abernethy Forest: the History and Ecology of an Old Scottish Pinewood" by Ron W. Summers (360pp; RSPB; ISBN: 9781999988203), a readable compendium of many aspects of the Forest, both its ecology (e.g. fungi, plants, invertebrates, mammals) and its human aspects (history, management). It is far too massive to summarise here, but some nuggets include: